I am writing from Banjarmasin, in South Kalimantan, one of the four Indonesian provinces on the island of Borneo. Banjarmasin, ‘the city of a thousand rivers’, is an urban edge in itself, settled on a delta island near the junction of the Barito and Martapura rivers. Banjar language is a result of the fusion of Malay and Dayak cultures in the area around 400 AD.

One of the many special things about Banjarmasin is Sasirangan, a resist dye technique that is similar to Japanese Shibori, but often uses motifs that represent the river and local plant life. The first Sasiringan designer I met here was Orie, who is inspired by the local riverside culture and by the natural environment. One of his award winning designs is called Seribu Sungai (Thousand Rivers). Another of the designs from his studio is of Pakis, which is a type of fern that grows on the edges of rice paddies. As well as being edible, pakis fixes nitrogen in the soil, so that the paddies are more productive. In the Sasirangan cloth design, the grid motif behind the pakis fronds represents the straight edges of the rice paddies, and contrasts with the organic curves of the fern. This design celebrates the relationship between people and plants in Indonesia.

Sasirngan is made by stitching cloth before dying it.

Orie told us (Jess Dunn and me) about Muhammad Redho (Pak Redho), an expert in natural dyes for Sasirangan, and we decided to find him. We had the instagram handle, the name of the shop ‘Warlami’, and an address, but using maps can be a bit hit and miss in Indonesia. Luckily we were walking, and when we felt we ‘should’ have already arrived, we asked at a house with a lovely garden if they knew the studio. The women were unsure but when Jess showed them photo of Pak Redho from instagram, they laughed … ‘Oh yes, we know his face and his house,’ but many people have that name here. They popped hijabs on (no need to change out of their pyjamas and house dresses) and started up their motorbikes. ‘We’ll take you there’.

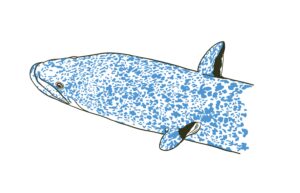

The seed pods of the lipstick tree

Approaching the house, the first thing I noticed was a beautiful tree I didn’t recognise. The fruits resembled rambutan, but are more flat and more bright. The tree is Kesumba Keling (Bixa orellana) and is originally from the Americas, where it is now sometimes called the ‘lipstick tree’. Kesumba Keling was planted in Indonesia for its pigment, to colour fabrics, paints and foods, before synthetic dyes almost replaced it entirely in the 1980s.

Indonesia’s rivers are in trouble, and the fish and plants are no longer healthy.

Pak Redho’s studio and home are nestled in a garden deep in the kampung. Many of the plants there are used for dying textiles. There are several large fishponds in the garden. ‘This is our proof,’ he says pointing to the fish, ‘that our dying processes are kind to the environment … Indonesia’s rivers are in trouble,’ he explains, ‘ and the fish and plants are no longer healthy’. In Kalimantan, and in Java, where Sungai Citarum is sometimes called the world’s most polluted river. (See http://www.austroindonesianartsprogram.org/blog/most-polluted-river-world-citarum-river-indonesia and https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-most-polluted-river-in-the-world-the-citarum-river.html). This is largely due to the textile industry, as well as untreated household waste.

The garden

Pak Redho is interested in processes that are kind to the environment. Other trees he has planted include an Ulin (Borneo Ironwood) sapling and a Pohon Perdamain (Barringtonia Asiatica), which has sentimanetal value to his family because it is also planted in the kraton in Yogyakarta where his wife is from.

To make a black dye, Pak Redho uses Rambutan skins, which he buys from people who sort rubbish. One kilo of rambutan skins cost him about rp7000 (AUD.7). As the rambuntan skins boil, they fill the air in the studio with a warm muddy scent. They are a earthy colour at first, and with the addition of an iron mixture if turn black, ‘like magic’ says Jess.

Freshly dyed cloths drying

0 Comments