Methodologies: Images

Seeing is a great deal more than believing these days. You can buy an image of your house taken from an orbiting satellite or have your internal organs magnetically imaged. If that special moment didn’t come out quite right in your photography, you can digitally manipulate it on your computer. At New York’s Empire State Building, the queues are longer for the virtual reality New York Ride than for the lifts to the observation platform. Alternatively, you could save yourself the trouble by catching the entire New York skyline, rendered in attractive pastel colours, at the New York, New York Resort in Las Vegas.

(Nicholas Mirzoeff 1998, p. 1)

As a way to introduce visual methodologies, this section gives a brief summary of some of the arguments that circulate in the discursive arena of the visual. A good starting point is Nicholas Mirzoeff’s opening of his ‘What is visual culture?’ in the now classic Visual Culture Reader, (1998) Mirzoeff claims that the visual, and visual culture, are central to contemporary societies not simply because we live in a world saturated by visual images, or because our understanding and knowledge are more likely to be mediated by images, but because our experience of the world is more visual and visualised than ever. Mirzoeff argues that this globalization of the visual has led both to interdisciplinary research and to the need to come up with new ways of interpreting the visual (1998, p. 4).

In the context of place-based methodologies this quote is important because Mirzoeff points out that the visual has acquired a central role in the way we experience, interpret, represent and even make places. This is not to suggest that the visual mediation of place is a new idea. There are many historical examples that could be made, from the way early cartographer used dragons and the sentence Hic Sunt Dracones (Here Be Dragons) to represent unknown and therefore thought to be dangerous places, like Fra’ Mauro’s Map of the World; to medieval maps of sea monsters; to Renaissance paintings of ideal cities in Italy (c.1470), or in the same years in Japan of Four Seasons in one landscape. Rather, what Mirzoeff suggests is that we increasingly understand place as a visual experience. Mirzoeff was writing in 1998, and in the following twenty years much more has happened in the way digital and social media have further enriched and complicated the way we interact with place. In his more recent work Mirzoeff returns to the theme of how we see, linking the way we see to all sorts of changes, from the social and political to the environmental and technological:

For all the new visual material, it is often hard to be sure what we are seeing when we look at today’s world. None of these changes are settled or stable. It seems as if we live in a time of permanent revolution. If we put together these factors of growing, networked cities with a majority youthful population, and a changing climate, what we get is a formula for change. Sure enough, people worldwide are actively trying to change the systems that represent us in all senses, from artistic to visual and political. (Mirzoeff 2015, p. 7)

Mirzoeff continues explaining how since the 1990s, when he published his first book on visual culture, the visual has migrated from specific places, like art galleries, cinemas and personal photos, into the world. Instead of having to go to go to the cinema for instance, you can watch a movie on any screen of your preference.

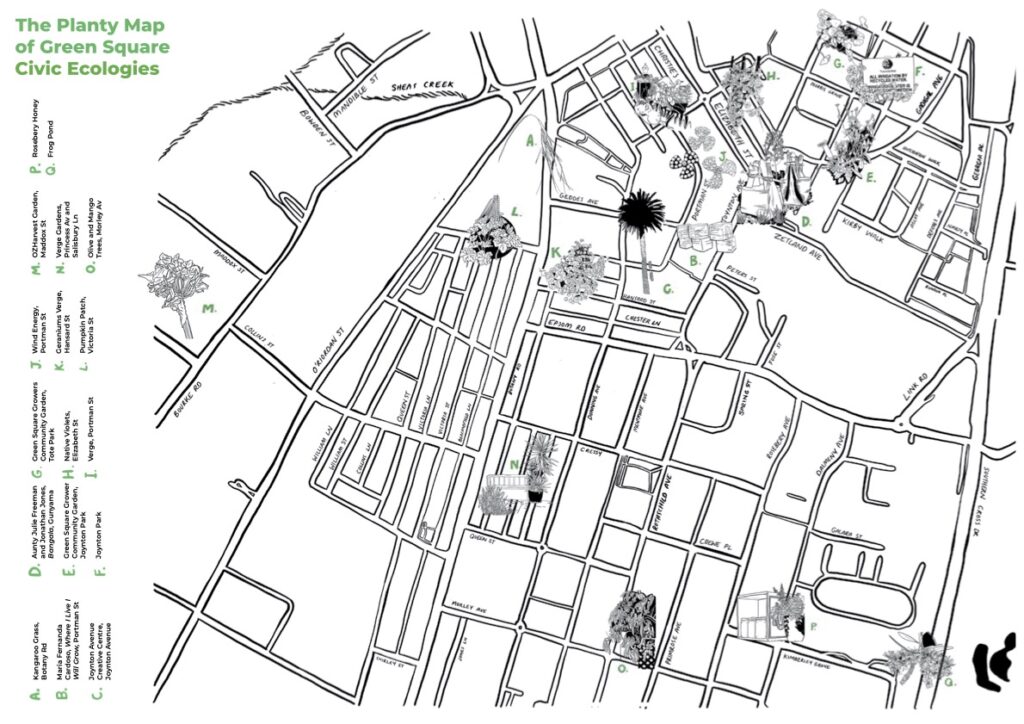

This means that the way we experience place is not simply mediated and represented by images, but that the presence of visual objects, digital or otherwise, has a crucial role in place making. Think for instance about the way you navigate a new city using apps: these apps have an active role in shaping the place you see, perhaps taking you through a route most used, or signalling certain landmarks, or layering specific information on your map, or maybe making you wander instead. This of course opens up all sorts of questions about who decides what we see and how to see it. In many Mapping Edges projects we decide, for instance, to give a representation of space based on plants, and to invite people to be led by plants on their walks.

Ella Cluter, The Planty Map of Green Square Civic Ecologies, 2021, detail.

Ella Cutler, The Planty Map of Green Square Civic Ecologies, 2021.

As visual objects migrate from specific sites into the world, attention to the visual has moved from disciplines such as art, art history, design, architecture, media studies, and film studies, to social research, geography, sociology. Gillian Rose, professor of Human Geography at the University of Oxford, speaks of disciplinary visuality (2003) to indicate both the way the visual is taken up differently by diverse disciplines, and the way in which in the specific discipline of geography there are multiple positions in regard to visuality (which can be defined as the way in which we see and how we are made to see the world, Foster 1998, p. ix). This is significant because it opens a critical reflection on visuality, visual methods and the study of space and place. In brief Rose reminds her readers that the way visual methods are used to study place is never neutral. What does this mean?

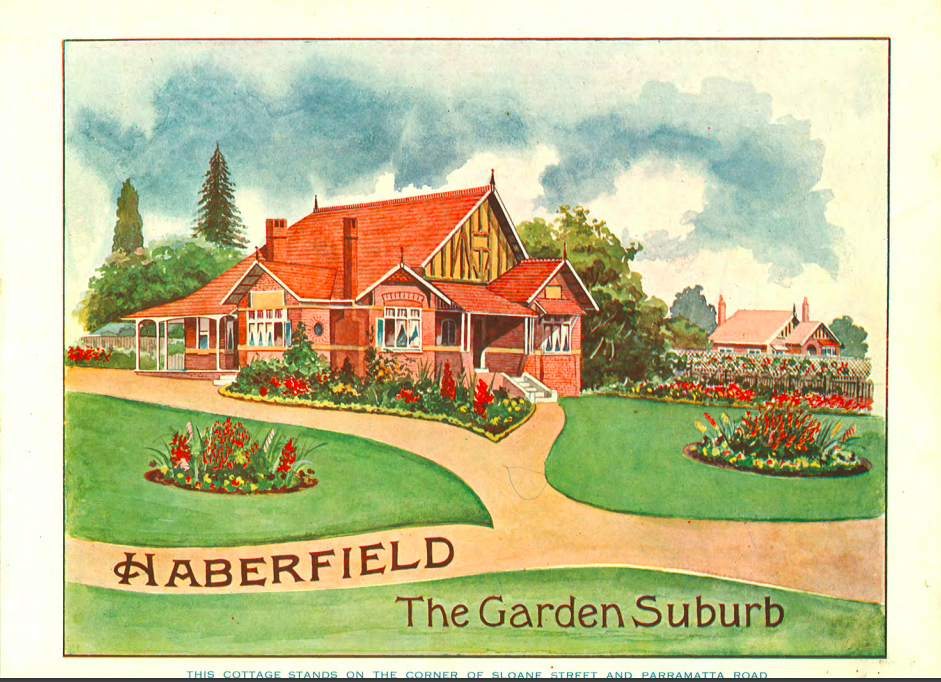

One of the historic images we analysed to research heritage in Haberfield.

Rose refers back to the 1980s renewed attention to culture as a key to understand social processes, identities, change and conflict. In particular Rose focuses on Stuart Hall’s definitions of culture and representation (1997). The underlying idea is that culture is understood as the production and exchange of meanings rather than as specific things and that people make sense of the world through these exchanges and interpretation. Hall writes:

Culture, it is argued, is not so much a set of things- novels and paintings or TV programmes and comics – as a process, a set of practices. Primarily, culture is concerned with the production and the exchange of meanings – the ‘giving and taking of meaning’- between the members of a society or group. (1997, p. 2)

Following this understanding of culture, Rose explains, ‘Whatever forms they take these made meanings, ore representations, structure the way people behave – the way you and I behave – in everyday lives.’ (2016, p. 2) As a consequence, according to Rose, the images circulating around us are not neutral, they offer a particular representation of the world, they show and interpret it in particular ways. We can take Tourism Australia campaigns as an example of representation in relation to place; these campaigns target an international tourism market they represent Australia mainly as coastal and aquatic environments, as food and wine destinations, or with a special focus on young tourists. This representation of Australia is probably quite different from what we experience in our everyday lives.

Another important point about visuality is that it is not just constructed (for instance like Australia is constructed as beaches and cliff walks for international tourists), it is also affected by positionality. One’s position is influenced by cultural and social factors, gender, class, ethnicity, and other aspects of identities. Positions have an effect on the way a person understand and knows, both in material and abstract terms. For instance, cultural theorist Mary Louise Pratt (1992) has researched travel writing in relation to European colonialism. One chapter is dedicated to the Victorian period, in particular to the way in which explorers saw and depicted Africa as part of the British colonial project. Some of the stylistics used to represent place in this literature included what she called mastery. This is the tendency to describe a place as if it was a painting, from a standpoint privileged both in social terms of class, gender and race (as explorers tended to be wealthy, white and male), and in geographical terms, as explorers tended to describe their scenes from the top of hills and mountains. This, Pratt argues, produced a masculine heroic discourse of discovery and conquest. But there were also women travel writers. Unlike male explorers, these women do not spend much time on promontories, and the heroic masculine discourse of discovery, and mastery over all that can be seen at glance, is not readily available to them. Instead women travel writers write from a position that is, geographically, in the thick of things, from swamps, river banks and deep in the vegetation. As a consequence, what they see, and what they depict, is different from the heroic description of mastery over the landscape (1992, pp. 201-216). This is interesting when thinking about visuality and place, because it shows the way a place is seen (and visually represented) is affected by social and cultural factors.

Positionality also affects different academic communities, and specific visualities are developed in different disciplines. An urban ecologist’s ways of seeing, but also looking and representing, a cityscape may for instance concentrate on the presence of plants native to an area, while an anthropologist may see and capture cultural practices or social relations, and a historian may appreciate the presence of elements from different periods in the same landscape.

Similarly, visual culture itself depends on positionality: on the social, historical, cultural and geographical factors that produce a particular definition of or take on visual culture.

Visual Objects and Epistemology

As we have seen above there is a strong argument that visuality is dependent on positionality. This argument is the result of feminist and postcolonial theories (Haraway 1991; Pollock 1988; Tuhiwai Smith 1999; Rose 2016). However, in other contexts and times photographic images and videos had been thought to be more objective research tools than textual or oral methods. In early anthropology (one of the first disciplines to use visual methodologies) photography was considered evidence: a truthful and simple record of phenomena, events, places, social relations and so on. But is photography really objective?

One way to ensure that photographs capture what research participants (as opposed to the researcher) see, for instance, is to give participants cameras to record what they see. But even this method has been critiqued for assuming that sight is ‘obvious’ and that there ‘is an absolute correspondence between the space of sight and the space of articulation’ (Kearnes 2000, p. 332). Against the assumption that an image can be or is a transparent and truthful representation, thinkers in poststructuralist intellectual traditions have argued that images construct reality, and that images can be read as texts to understand wider social and cultural practices and formations (Knowles and Sweetman, 2004, 5-6). Vision itself has been analysed as a historical construction (Crary 1990), and as gendered (Pollock 1988), and in relation to visuality (Foster 1988). More recently Crang has argued that it is precisely because notions such as transparency are problematic that visual methodologies can be deployed to interrogate and disrupt ways in which knowledge is visually constructed, including knowledge about place. He suggests a three-fold approach: first, to use aesthetic registers to emphasize modes of creative knowledge making. Second, to embed participatory and critical visual methodologies in local culture so that people can use them according to their own priority. And third, to point to the limits of representation (Crang 2010, pp. 208-224). Examples of these three points are also explored in Megan Heyword and Susie Pratt’s podcasts.

Visual Objects and Digital Technologies

Donna Haraway reflecting on the spread of visualising technologies in sciences, such as medical imaging, satellite surveillance systems and so on writes that this ‘technological feast becomes unregulated gluttony; all perspective gives way to infinitely mobile vision, which no longer seems just mythically about the god-trick of seeing everything from nowhere, but to have put the myth into ordinary practice’ (1991, p. 189). To counter this aspiration to the god- trick eye that sees all, Haraway proposes a different kind of objectivity that takes into consideration positionality, or situatedness:

Feminist objectivity is about limited location and situated knowledge, not about transcendence and splitting of subject and object. In this way we might become answerable for what we learn how to see

(Haraway 1991, p. 190).

This is important to study place, because it proposes alternatives to the way we know and experience the world beyond mainstream representations, and this in turn opens up to more creative and critical solutions. Haraway in the same essay invites us to recognise two things. First, that the way we know and experience the world is with our bodies and second to understand that our bodies are in a limited location and in an always situated knowledge is a step towards objectivity. To make her point Haraway asks us to take into consideration how others may see the same landscape we see, for example how her daily walk looks like to her dogs, who have limited colour vision, but a greater area for processing smells; or how it looks through the compound eyes of insects. In doing so Haraway proposes to avoid politics of fixed self-identity (a bad visual system) and adopt instead a mobile and changeable positioning to embrace a ‘generative doubt’ (1991, p. 192). In brief, Haraway invites us to consider a multiplicity of visions and visualities to counter the all-seeing eye of master narratives. As researchers of place using visual methodologies this can be translated for instance in a variety of points of view (or POV, figuratively as well as literally), as critical visual narratives from below, as visual essays that embrace other species as well as humans, just to make a few examples.

Although Haraway was writing in 1991 this discussion is still relevant today in the context of the emergence of new digital technologies. Digital media enhance both the ‘god-trick of seeing everything from nowhere’ (1991, p. 189) and multiple seeing positions through immersive experience with no fixed view point. For example consider the shifting POVs in the BMX/Parkour video enabled by a GoPro and how in this video we understand place as immersive, and how the GoPro translates not only vision but also the sense of movement.

According to Gillian Rose, who recapped the relevance of Haraway to debates on emerging digital technologies (2016, pp. 12-14), visual culture and mobile vision are enmeshed in power relations: they are only available to some people and institutions. As such digital technologies produce a hierarchy of seeing positions according to one’s class, gender, race, sexuality and so on. Some institutions (like governments, the military, corporations) for instance claim to see with universal relevance (think about surveillance systems), while many people are the subject of this gaze (for instance, you being body-scanned at the airport). These processes of visual categorization are both representational – they give specific meanings to images -and non-representational – they produce specific experiences from images. Images make visible or invisible social differences, not just literally portraying poverty or wealth or whiteness, but determining what, why, when and how something is seen or not.

In opposition to this, other organisations deploy participatory ways of making specific things visible. Public Lab, for instance, ‘is a community where you can learn how to investigate environmental concerns. Using inexpensive DIY techniques, we seek to change how people.

Images and Research

Images are used in research in a variety of disciplines from anthropology to health studies to film, and to cultural studies. Each discipline has a specific understanding of how images should be used in research. Some disciplines use images as means of data collection. For instance, a landscape architect may use maps to annotate her or his observation on a certain site (as Andrew Toland explains in his podcast). Other discipline may use images for data analysis (as Lesley Harbon elucidates here in her podcast on linguistic landscapes). Others again may use images to communicate research (listen for instance to Alexandra Crosby’s podcast on using Instagram and Megan Heyward on creative methods and mobile apps). Cultural studies scholars and geographers (you can listen to Angela Giovanangeli, Paul Allatson, Kristine Aquino and Carolyn Cartier podcasts) may use visual methodologies to research places, such as museums, or cities. In general, we can think of two general ways of using images in research: as ‘found’ images that we use as data, or as images that we make as research data. Within these two vast categories there are many methods that can be employed, as Gillian Rose briefly explains in this video. Some of these methods are connected to specific disciplines. Art historians, to make an example, do stylistic and content analysis; people working in advertising may prefer a semiologic analysis; cultural studies scholars may produce discourse analysis. Often methods are mixed. What follows is an arbitrary selection of some of the methods that in my experience are most used and useful for UTS students: if you are curious and wish to know more please have a look at Gillian Rose, Visual Methodologies (2016) and the book’s companion website, which is a treasure trove of resources.

It has become a common practice to make photographs as research data. Some of the ways photography is used include to document processes; as a visual research diary; to record things, landscapes, streetscapes; to capture many different details of a scene; to frame a subject in a certain way; to reveal characteristics of a subject; to ‘construct’ a subject according to the conventions of a given genre (for instance if I am taking photographs of a mountain I might want to use landscape photography conventions – and be aware that they might be different according to culture and even country) to make just a few examples.

Whatever the reason for choosing photography as a way to make research data, there are some important technical points to keep in mind. In other words, it helps if you can take a good photo. A good photo is not a matter of like or dislike: some elements help to make an image readable. To mention a few:

- Straight lines versus lopsided lines: horizons are horizontal and vertical lines should be at 90 degrees, unless you are trying to convey some form of movement (otherwise the image topples over).

- Focus: which element is important in your composition?

- Composition: frame your photo so that the important elements are clearly in it, and make sure that there are no busy details around the margins of your frame.

- Sharpness: it helps to read an image if it is not blurry (unless you want to convey blurriness). See the world in environmental, social, and political terms’ (https://publiclab.org/). Using balloons Public Lab mapped oil spills in the Mexican Gulf, producing more updated and detailed maps than governmental organisations through a crowd-sourced process based on DIY tools (like balloons and kites) and open source software.

- Light: make sure there is enough light, where does it fall? Is the subject of your image visible?

These are just a few of the things to keep in mind. Clearly this is not the right place for a ‘how to take a photograph’ discussion, but there are many excellent photography courses online, both for people wanting to use a camera or their phone camera.

Some of the podcasts in the Place-based Methodologies series explore the use of visual in combination with other methods. Paul Allatson uses visual, textual and sensory analysis to understand texts and contexts in his work on Latin@ cultures in U.S.A. Angela Giovanangeli relies on a combination of observation, interviews, textual and visual analysis and photo-documentation to examine cities. Kristine Aquino mixes photography and ethnographic methods in her studies of multicultural spaces. Carolyn Cartier employs photography as one of the ways to explore and document change in cities in China. Clancy Wilmott works with video as a form of collaborative mapping to explore people’s relations and interactions with place. Susie Pratt adopts a pragmatist approach and lets methods emerge through the inquiry process, asking ‘what if’ questions to find out how people interact with the environment. Emma Fraser uses multiple methods such as ethnographic fieldwork and visual methods to understand place from a variety of perspectives, and crucially always designs her methodologies starting from the specific topic she is investigating. Finally, Leyla Stevens’ practice-based work is based on the use of still and moving images to animate forgotten histories of Bali.

Photo Documentation

Photo documentation is a method used in diverse disciplines to record large quantities of data, often with the intention of capturing the way in which social and cultural practices and change are inscribed and embedded in the landscape. The data captured through photo documentation is then analysed. Photo documentation assumes that photography is an accurate technology to record what one sees. This assumption, however, is highly contested, as we have seen in the introduction. Professional photographers, who understand photography to be a technology to ‘make’ images rather than ‘take’ images, also tend to disagree about the ‘naturalness’ of photography. For instance in the project The Corners the photographer Chris Dorley-Brown takes multiple exposures of the same scene at different times, creating vivid images of street corners. This technique allows him to superimpose in one single image people who in reality might have been in the location depicted in the photograph on different days and at different times.

In addition to this, starting in the early 2000s, social scientists began to recognise that reality is messy (Law 2004) and that imposing neat research methodologies on reality would inevitably lead to a partial representation of the mess. The messiness of life itself would not be captured.

The idea of mess is important when we are considering using photo documentation:

- Can we capture the messiness of place?

- Does the technology available to us make it possible?

- What about the elements we deliberately leave out of photographs because they do not match our idea of the subject we are photographing?

- Can we capture the trajectories that animate a place? And do we need a specific research process?

Gillian Rose (2016, pp. 310-313) uses as an example the work of Charles Suchar on changes to the urban environment. Suchar worked specifically on gentrification in Chicago, and he focused on the material changes both to streets and home decoration that resulted from gentrification (see for instance Suchar 2004). Key to this process is to establish clearly a link between the conceptualisation of the research topic and the photographs that are being taken. Suchar explains his process as shooting from a script. ‘Shooting scripts’ he writes ‘are a series of questions about the subject matter or a photo documentary project.’ (1997, p. 36). To explain shooting scripts he refers to one of the most famous documentary photography projects in U.S.A., the documentation of the 1930s great depression managed by the Farm Security Administration (FSA) a New Deal agency founded to combat rural poverty. The shooting script on life in a small town in rural America included these questions:

“Where can people meet?”, “Do women have as many meeting places as men?”, “How do people look?”, “How much different do people look and act when they are on the job than when they are off?”, “How do the homes look inside and outside?’ (1997, p. 36).

These are also the type (obviously not the content) of questions that can be used in your projects.

Suchar continues with examples from his own work on gentrification, focusing on the effect of commercial changes on the physical, material and social lives of selected streets in Chicago. To guide his shooting, he prepared an initial script with questions such as:

- What variety of stores or businesses are to be found in different market strips, located in different areas of the community?

- What do they sell or what services do they provide?

- Who are the customers or clients who are served by these establishments? Are they locals or people from outside the neighbourhood?

- Who works, owns, or manages these establishments? (1997, p. 37)

For each question, he shot many photographs, and at the same time wrote extensive field notes detailing how each image was a response to a question. He did so using analogue technologies. Today we can follow a similar process using digital technologies, as I explain in the next section. According to Suchar the next important step is coding images. Codes are descriptive words that ‘categorise series of otherwise discrete events, statements, and observations which they identify in the data. Researchers make the codes fit the data, rather than forcing the data into codes’ (Charmaz cited in Suchar 1997, p. 38).

Coding is important to see what kind of pattern emerges from the photographs and to revise the initial shooting script, as Suchar suggests:

At the completion of a coding session, I review the provisional labels, codes and attached narratives and ask the following basic questions: What possible answers to this question have yet to be explored? What other questions do these answers raise? Inevitably, new leads to answering original question arise and some new questions, either more focused than the first Grounding Visual Sociology Research in Shooting Scripts or perhaps wholly different, direct the project to the next stage of photographic field work. Finally, it may be that the original questions asked in the script are still in need of more detailed photographic answers. I then revise the shooting script according to the grounded theoretical analysis in order to accommodate these questions. (1997 pp. 39-40)

Other scholars, such as Jerome Krase and Timothy Shortell, advocate a different process, which involves taking a photographic survey of a given neighbourhood, without trying to capture particular content or aesthetics. ‘Like the ethnographer collecting observational data, this method produces a lot of visual information in the field, the significance of which may be known only later, upon reflection.’ (Krase & Shortell 2011, p. 372) this process also involves multiple trips, and the making of an extensive visual archive of a particular site, such as the archive of vernacular landscapes they maintain. A large quantity of data enables the researcher to see emergent patterns, to compare them across different locations and to relate then to social and cultural processes, practices and change.

In conclusion photo documentation does not mean merely taking photographs and hoping they will document a place, or social or cultural processes. Rose has a word of warning that without a rigorous system, such as the ones described above, there is a risk of ending up with photographs that are only illustrations, rather than a critical visual methodology (2016, p. 314). A similar reflection should be applied to Instagram as a research tool, as we will see in the next section.

Using Instagram to Make Research Data

Digital technologies, both in terms of hardware and software, mean that large numbers of people can make images, and indeed they do: in 2022 there were more than 2 billion Instagram users. Statistics like these have led researchers to argue that digital technologies reframe social and cultural interactions and that digital devices have become central to social life in many locations ‘reworking, mediating, mobilizing, materializing and intensifying social and other relations.’ (Ruppert, Law & Savage 2013, p. 24). This realisation has prompted a number of questions on the ways we know and understand the world: digital devices and the data they generate are both the material of social life and are means and part of the ways we know these lives (2013, p. 25). For instance, Instagram is both a material part of our everyday life (as its interface, filters, tags, images, social relations created through following or not following and so on) and one of the ways we know everyday life (I might use Instagram to find a good place to have cake). Instagram has also shaped some places so that now some designers think of Instagram friendly solutions: particular designs that will look good on Instagram. Listen to the story of how a building designed as an affordable working space in London, the Yardhouse, became an instant Instagram success in this 99% Invisible episode.

Moving this general reflection on the transformations brought about by digital device into a critical reflection on methods, Ruppert, Law & Savage (2013) stress the importance of understanding the specific qualities and affordances of individual digital devices (device here means both hardware and software, so for instance a phone and Instagram). Ruppert, Law and Savage also note that are different modes in which digital devices are used as part of research methods: some can adapt existing methods, such digital ethnography, some might develop new methods, such as cultural analytics (2013, p. 30). In this video Sarah Pink explains digital ethnography as an example of how the digital reconfigures existing methods and also changes existing notions such as embodiment, and more importantly for place-based methodologies, ideas of place. As an example of how digital devices produce new methods to understand place, Lev Manovich explains his team’s project, Visual Earth, ‘the first study to analyse the growth of image sharing around the world in relation to economic, geographic, and demographic differences’ in these terms:

We use a unique dataset of 270 million geotagged images shared on Twitter around the world between 09/2011—06/2014. In addition to analysing all these posts worldwide, we look in detail at image sharing in 100 urban areas situated on six continents. Rather than only considering the world’s largest cities or capitals, we selected these cities using different criteria to better represent the diversity of urban life today. We started with a list of 500 urban areas with at least 1 million people. We then chose 100 cities from this list. The cities in our list vary in size, history, culture, and global importance; they are situated on all five continents in countries with different levels of economic development. (2017, n.p.)

Both these examples, digital ethnography and cultural analytics, are based on a clear understanding of the specific qualities of the medium, and of the tools at hand. What happens if we apply the same thinking to using Instagram? What can Instagram do that is new, in comparison to photo documentation?

Mapping Edges, as illustrated by Alexandra Crosby in her podcast, uses Instagram as a note-taking tool, visual archive, and as engagement platform. We use our phone cameras with a variety of apps (but we do not shoot with Instagram) to take visual notes. We also shoot using DSLR cameras, which give us more flexibility in terms of how to make a photo. New cameras with WIFI connections enable us to connect to our phone and share images on Instagram in real time. One feature of Instagram is filters and editing tools. These can be used to give the image a specific look, texture and atmosphere. Using captions wisely we can write a short description of what is important in that specific image. Instagram also enables us to tag the content we shoot, and to make it searchable (see also coding). For instance, when I shoot using #mappingedges I add other hashtags to narrow down what the photograph is about, tags such as #gardening or #design or #dragonfruit. This process is similar to coding, and it also connects our images to those of others who use the same hashtag. In this way images are distributed, and become part of a network. Others can contribute their knowledge about specific posts, for instance one of our first photos was of a plant we did not know. Within a few hours someone had identified the plant. Similarly, the use of the hashtag #mappingedges has created a small community, with more people starting to use it.

Mapping Edges uses instagram as a collaborative note taking and archiving tool.

Instagram as a research tool is described by ethnographer Tricia Wang in this article. Wang reports on her ethnographic fieldwork in China, and defines her use of Instagram posts as live fieldnoting. Similarly, Megan Heyward describes the way she uses a camera while walking in a city as a form of live writing here. The second part of Tricia Wang’s article offers practical examples of how to build a visual archive on Instagram including travel, observations about the built environment, about social interactions in a given place, people, and as documentation of the research process itself (2012, n.p.).

In summary: Instagram’s affordances reconfigure photo documentation in specific ways: images can be 1- stored online; 2- tagged; 3- captioned and annotated; 4- distributed in real time; 5- shared; 6- networked.

Practical Tips for First Timers

Any study that involves other people must be based in the understanding of research ethics. Undergraduate students usually do not need a formal application to a university Human Research Ethics Committee, however it is a good idea to read the National Statement on ethical conduct.

Toolkit audit:

- Which tools will you use?

- Are they in working order?

- Are batteries charged?

- If you use a camera, which lenses will, you use?

- Do you need a tripod?

- Do you have an app or notebook to take notes?

- It is a good idea to visit the site you intend to photograph first, to understand how to get there, and get a feel for the place. If you need to walk for long distances consider which shoes you are going to wear.

- Do you need to ask for permission to take photographs? Legally if you are standing on public land you are allowed to take photographs of whatever you want. However, if you are photographing people it is a matter of good ethics and good manners to ask for permission. You can print out and take a few of the project information sheets.

- Have a clear set of questions in your mind and develop a shooting script.

- Let these questions tumble at the back of your mind as you are shooting.

- Remember to shoot good quality photographs, at the highest resolution.

- Take notes as you go: why did you take a certain image, what elements are important, and so on. Instagram is an excellent platform because it allows tagging. Once you have finished shooting you need to process and save your images. There are different management systems you can use: listen to Andrew Toland explaining how he manages images in his podcast.

- Code, or tag, your images.

- Review your archive: what is emerging? Do you need to refine your questions and organise a second visit?

Photo Elicitation

(The description of this method was written by Dr Deborah Nixon)

Using photographs in research is a powerful way to connect interviewee and interviewer and to elicit affective and rich responses to interview questions. Photo elicitation as a methodology involves the ‘simple idea of inserting a photograph into the research interview’ (Harper 2002, p. 13). John Collier, an anthropologist, first coined the term ‘photo elicitation’ in 1957. He was an early practitioner and researcher into the efficacy of the use of photographs in interviews. Collier argued that photographs could initiate reflections and yield data that were often hard to extract through structured interviews. He identified the value of this methodology as laying in the unique return of insights that might be impossible to obtain through other techniques (1967 p. 46).

Collier analysed the affective quality of the responses he recorded both with and without photographs and concluded that the former was the most fruitful method. One of the factors he (1967, p. 47) identified was that the ‘informant’ felt less like the subject of the research allowing for a discussion to flow between the researcher and the ‘informant’ about the object (the photograph). Collier (1967, p. 47) refers to ‘memory trauma’ or the process of going around in circles attempting to recall details and dates, without this pressure the images do not replace memories they help to connect them. Photographs evoke an affective response they can help to stimulate memory, feelings and knowledge of an experience (Berger cited in Harper 2002, p. 13) that simply asking questions may not yield.

I refer to this disruption to a linear story as ‘getting off script’ particularly when participants are being interviewed about biographical information. I found that there was a tendency in elderly interviewees I interviewed for my research to be restrained within the confines of a linear narrative around biographical details when a richer entry point could be created by photographs of places that related to the time or experiences being explored. This also brought into play memory, nostalgia, and responses to places over time.

The forms and usages of the images, who makes them, or whether they are from an existing archive, such as a family album is driven by the purpose of the researcher’s project. Rose’s (2012, p. 305) chapter on photo-elicitation is limited to looking at ‘images that are made as part of a research project’ and not with introducing existing images into interviews. Collier and Collier (1986) on the other hand photographed the communities they were researching because to particular images in interviews they found that this helped to build rapport. As Rose, points out there are myriad ways to use and interpret images and this has resulted in a broadened range of opportunities for interpreting visual data. On the other hand, Pink (2001 p. 20) advocates for the involvement of the researcher at ground level suggesting that they too are under scrutiny and that subjectivity is an enriching part of engagement with interviewees.

In my research I used photographs in interviews to act as a ‘meeting point between personal and professional identities…in situations where individuals may want to express different aspects of their identities’ (Pink 2001, p. 26). Looking at photographs with interviewees brought us together in the intimate exercise of connecting the here and now to the ‘there and then’ of the photographs of the place we were located in.

Photographs also introduced an unexpected haptic element into the experience of my photo elicitation interviews. Although, Marks (2000) is referring to the way film works on a sensual level her description of haptic visuality as a way to ‘[see] the world as… appearing to exist on the surface of the image’ is something that images do. For example, I witnessed one of my interviewees touching the surface of a photographs as if that small poignant gesture could transport her back to the time and place captured therein.

In summary, in some situations photo elicitation coupled with unstructured interviews can work as a powerful method for unlocking thoughts, memories, sensations, experiences and connections to and about places in a way that structured interviews cannot.

Practical Tips for First Timers

- Any study that involves other people must be based in the understanding of research ethics. Undergraduate students usually do not need a formal application to a university Human Research Ethics Committee, however it is a good idea to read the National Statement on ethical conduct.

- Be clear about your purpose – why have you chosen this methodology? Ask yourself whether this methodology will enhance your interview data.

- Decide how you want to deploy photo-elicitation into your field research.

- If you decide you want to use your own photographs or images you need to consider what is driving your own choices.

- Make sure the photographs are of a size that the elderly or others with vision problems can see. I found that simple A4 prints worked best for my work.

- On the other hand, if you decide that you want to ask participants to take photographs of a particular place in order to capture or represent what it means to them, then you must consider what equipment (apart from a mobile phone) may be needed and be clear about the task you set.

- Above all you need to be sensitive to the feelings and levels of expertise in your interviewees and find the methodology that works best for all on an ethical level.

A Speculative Exercise

- Take your neighbourhood as an example and use photography to document how it changes over a period of time.

- Do a preliminary walk taking snapshots.

- Identify which elements are recurrent in your snapshots, and choose a couple. For instance, it could be that the colour blue seems to become prominent, or that certain shapes are visible in multiple locations, or that people wear a particular style in one part of the neihbourhood but not in another.

- Based on the emerging themes can you write shooting script?

- How will you conduct your inquiry? Which tools will you use?

- How will you present your findings?

- Which broader spatial, social, environmental and cultural issues are at play?

- Can you identify local and global trajectories that traverse your neighbourhood? How are they visible in the landscape?

References

Anzillotti, E. 2016, ‘The Likeways App Encourages Users to Walk Around and Discover Their City’, CityLab, viewed 13 June 2018, <https://www.citylab.com/life/2016/02/this-app-will-turn-you-into-an-urban-wanderer/470577/?utm_source=SFFB>.

Collier, J. 1967, Visual Anthropology: Photography as a research method, Holt Rinehart and Winston, New York, NY.

Crang, M. 2010, ‘Visual Methods and Methodologies’, in D. DeLyser, St. Herbert, S. Aitken, M. Crang & L. McDowell (eds),The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Geography, Sage, London Thousand Oaks New Delhi Singapore.

Crary, J. 1990, Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century, October Books.

Foster, H. 1988, Vision and Visuality, DIA Art Foundation Discussions in Contemporary Culture, The New Press, New York.

Hall, S. 1997, Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, S. Hall (ed.), Sage Publications Ltd, London.

Haraway, D. 1991, ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’, Simians, cyborgs and women: the reinvention of nature, Free Association Books, London, pp. 183–201.

Harper, D. 2002, ‘Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation’, Visual Studies, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 13-26.

Kearnes, M.B. 2000, ‘Seeing is Believing is Knowing: Towards a Critique of Pure Vision’, Australian Geographical Studies, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 332–40, viewed 9 May 2018, <http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/1467-8470.00121>.

Knowles, C. & Sweetman, D. (eds) 2004, Picturing the Social Landscape, Routledge, London and New York.

Krase, J. & Shortell, T. 2011, ‘On the Spatial Semiotics of Vernacular Landscapes in Global Cities’, Visual Communication, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 367–400, viewed 11 June 2018, <http://journals.sagepub.com.ezproxy.lib.uts.edu.au/doi/pdf/10.1177/1470357211408821>.

Law, J. 2004, After Method: Mess in Social Science Research, Routledge, London and New York.

Louise, P.M. 1992, Imperial Eyes. Travel Writing and Transculturation, Routledge, London and New York.

Collier, J. and Collier, M.1986 Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method, Albuquerque, UNM-Press.

Marks, Laura U. 2000, The Skin of Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses, Duke University. London, Sage.

Mirzoeff, N. 1998, The Visual Culture Reader, 1st edn, Routledge, London and New York.

Mirzoeff, N. 2015, How to See the World, Pelican Books, London.

Pink, S. 2001, Doing Visual Ethnography: Images, Media and Representation in Research,

Pollock, G. 1988, Vision and Difference Feminism, femininity and the histories of art, Routledge, London and New York.

Rose, G. 2003, ‘On the Need to Ask How, Exactly, Is Geography ‘Visual’?’, Antipode, vol. 35, pp. 212–21.

Rose, G. 2016, Visual Methodologies. An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials, 4th edn, Sage, Los Angeles London New Delhi Singapore Washington DC.

Ruppert, E., Law, J. & Savage, M. 2013, ‘Reassembling Social Science Methods: The Challenge of Digital Devices’, Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 22–46, viewed 12 June 2018, <http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0263276413484941>.

Suchar, C.S. 1997, ‘Grounding Visual Sociology Research In Shooting Scripts1’, Qualitative Sociology, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 33–55.

Tuhiwai Smith, L. 1999, Decolonizing Methodologies Research and Indigenous Peoples, Zed Books, London & New York.

Wang, T. 2012, ‘Writing Live Fieldnotes: Towards a More Open Ethnography’, Ethnography Matters, viewed <http://ethnographymatters.net/blog/2012/08/02/writing-live-fieldnotes- towards-a-more-open-ethnography/>.

Websites

99% Invisible, https://99percentinvisible.org/

Brooklynsoc, Visual Sociology from Jerome Krase and Tim Shortell, https://brooklynsoc.blog/

Public Lab, https://publiclab.org

Visual Earth, http://visual-earth.net/