This week Mapping Edges co-facilitated the Composting Feminism reading group with Abby Mellick Lopes. We read Tim Ingold’s 2004 essay ‘Culture on the Ground: The World Perceived Through the Feet’ and ‘Rising and Falling: The Theorists of Bipedalism’, one of the essays from Rebecca Solnit’s 2001 book Wanderlust: A History of Walking.

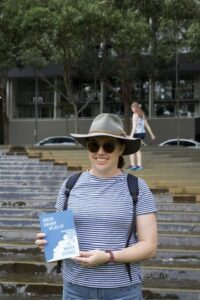

Rereading Wanderlust for the reading group was an absolute pleasure. Reading Solnit is like going for a walk with an old friend, even if you are reading her for the first time. Solnit uses such interesting stories as examples and has such a clever way of placing herself in each of them, reminding the reader that histories are embodied and that through texts, as when walking, we are thinking together as well as separately. ‘Walking…’ she says, ‘is how the body measures itself against the earth.’

We were interested in this particular essay because of how it relates to Ingold’s writing on walking. Ingold begins his essay ‘Ways of Mind-walking: reading, writing and painting’ with a quote from Wanderlust: ‘To write is to carve a new path through the terrain of the imagination . . . To read is to travel through that terrain with the author as guide’ (Solnit 2001, 72). He extends Solnit’s analogy to ask the difference ‘between walking on the ground, in the landscapes of “real life”, and walking in the imagination, as in reading, writing, painting or listening to music?’

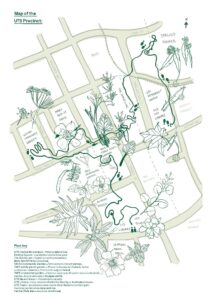

As such this essay is about how walking activates the imaginary, and how we translate sensing and thinking between the physical environment and the terrains of the imagination. ‘Perhaps it is the very notion of the image that has to be rethought,’ suggests Ingold, ‘away from the idea that images represent, on another plane, the forms of things in the world to the idea that they are place-holders for these things, which travellers watch out for, and from which they take their direction. Could it be that images do not stand for things, but rather help you find them?’ (16). This line of thought resonated with the fieldwork we have been doing as Mapping Edges, in particular the way we use photographs to take notes on the sensory ethnography we are conducting. As we have discussed elsewhere, the images we produce circulate through social media networks (twitter, instagram, wordpress). As such, despite what they seem (‘you take so many photos of plants’, said a friend visiting from out of town who follows me on instagram) these are not images that represent plants, rather they are ‘place-holders’, notes of the direction from which I was sensing the world at that moment in space. The walking and photographing we do together as Mapping Edges involves routines – arrange a time and place, one foot in front of another, photograph, label, share, wait for each other, continue – but also the flow of a changing environment where objects unfold, ‘explode and mutate’ (Knorr-Cetina 2011, p.191).

To return to our reading group, fellow composters were frustrated with Ingold. If writing is a kind of walking, Ingold can seem like a leisurely 18th Century gentleman ‘taking the air’. While there was some reflection on Solnit’s analysis of walking and, in particular, the way walking is gendered both in public space and in evolutionary history, it was Ingold’s essay that raised the most questions for the group. These included:

- Is Ingold’s evolutionary narrative plausible or relevant?

- How does walking remake and repurpose things?

- How does walking disrupt the city? And does Ingold understand psychogeography?

- How can theories of walking be more inclusive of people who can’t walk? What about rolling and other ways to move?

- What do we need to discard to understand the histories of our bodies?

- How can we become more skillful at using our feet? And other senses?

- How do different places produce different ways of walking?

Certainly this last question is very important to Mapping Edges, along with the way different cultural contexts delegate walking to different groups of people, for example to poor people. The valuing and devaluing in different societies, and the way Ingold urges us to think about walking materially (through shoes, paved surfaces and chairs) for me linked to the ever current issue of urban planning.

I recently watched ‘Citizen Jane’ (2016), a documentary about Jane Jacobs who campaigned against planning decisions in New York City that prioritized the motorcar (freeways) and ‘cleaned up’ the city (the projects) during the ruthless redevelopment era of the 1960s. What struck me about this story was that Jacobs recognised that walking, not driving made cities safe and vibrant. In her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, she famously argued for an approach to safe streets that included protecting public space and designing for pedestrians. This wasn’t a brilliant film. The rhythm of the story was off balance and it needed a different kind of sound design, but Jane Jacobs’ is an important hero of walking, and watching the archival footage of her world is great fun. Her work inspired a lot of community organising all over the world and still inspires people to value walking, see for example Jane’s Walk.

In Sydney, the lack of public interest planning sadly point to how little has changed since Jacobs made such compelling arguments for people-centered cities. Sydney could be one kind of Sydney or another, as made so clear by those campaigning to Keep Sydney Open and Stop West Connex. We know that top down planning decision produce unsafe, unhealthy and unsustainable cities. Walking makes this most obvious when you are trying to navigate on foot from one neighbourhood to another across the M4, M5 or any other freeway or when you are wandering through a deserted corner of the CBD late at night. Walking also reminds us that cities are not made by planning documents, artist impressions and real estate deals. They are made through our feet, in our imaginations, and in our conversations.

Ingold, T 2004, Culture on the ground: the world perceived through the feet. Journal of Material Culture, 9(3): 315-340.

Solnit, R 2001, Rising and Falling: The Theorists of Bipedalism, in R. Solnit’s Wanderlust: A history of walking. Penguin, pp. 30-45.

Ingold, T 2004, Culture on the ground: the world perceived through the feet. Journal of Material Culture, 9(3): 315-340

Solnit, R 2001, ‘Walking After Midnight: Women, Sex, and Public Space’ in R Solnit’s Wanderlust: A history of walking. Penguin, p.232-239.

Ingold, T 2010, ‘Ways of mind-walking: Reading, writing, painting.’ Visual Studies, 25(1): 15-23.

Knorr-Cetina, K. 2001, ‘Objectual Practice’ in Schatzki, T., Knorr Cetina, K. and Von Savigny, E. The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory. London, Routledge, pp. 184-197.

Jacobs, J., 2016. The death and life of great American cities. Vintage.

0 Comments