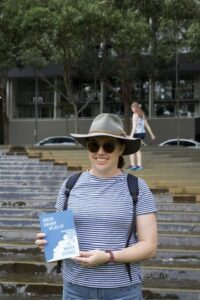

This post is not exactly about reading books, although books are present, but about reading an installation and a major art event through the lens of permaculture. The photo above is from the project Unpacking My Library at the 57th Venice Biennale. Inspired by Walter Benjiamin’s 1931 essay, this project allowed all participating artists (including dead ones, it seems) to list their favourite books. The books were then made available in the Stirling Pavilion at Giardini. This is from Bonnie Ora Sherk’s library: Deborah L. Martin, Rodale’s Basic Organic Gardening: A Beginner’s Guide to Starting a Healthy Garden, 2014. Other books included Gregory Bateson’s Steps to an Ecology of the Mind (1972) and Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird’s The Secret Life of Plants (1973). Clearly a good start to think of a giant international art event, systems and plants.

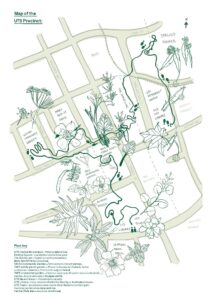

The 57th Venice Biennale involves as always a lot of walking around, and while I was walking I thought of what the Biennale would look like if I read it as permaculture zones and if I concentrated on its edges. The way the Biennale is distributed in the city of Venice lends itself to this kind of reading. It was originally organised at i Giardini around a zone 0, the central pavilion, surrounded by intensely structured – architectonically, curatorially, politically and symbolically – zones 1 and 2, the national pavilions. Reflecting processes of transculturation and global connections, disconnections, flows, hops and stops, this original late 19th century (1895) spatial organization based on nation states has been more recently extended to a second site, our zone 3, the Arsenale, and then to zone 4 and 5 off-site shows, collaterals, installations in the city and in nearby islands. Arsenale, as a zone 3, is an edge between the national pavilions’ zones 1 and 2 and the less structured off-site and collateral shows. Arsenale is also, in my twenty + years experience as a Biennale goer, where some of the most surprising works are. This year Arsenale is curated in nine ‘pavilions’ which kind of blend into each other around multiplicity, complexity and the role of the artist, or as Dan Fox writes in his review in Frieze, ‘it’s about pretty much everything.’

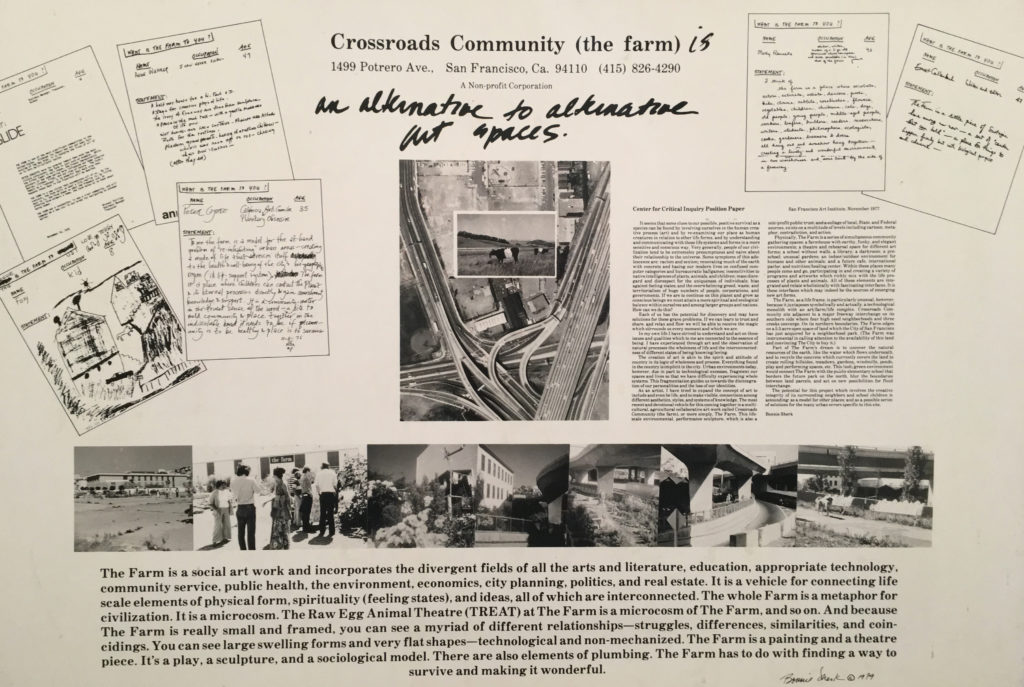

But I am not here to write a review of the Biennale as such, but rather to share some thoughts around a body of works that are edges between art (specifically art as social practice) and environmental stewardship and in keeping with my permaculture reading of the Biennale I want to write about Bonnie Ora Sherk’s installation of the documentation of her projects, Crossroad Community (the farm) and A lIving Library A.L.L. I think, and hope, Bonnie Sherk would appreciate zoning the Biennale and considering its edges. Her works, documented in an installation titled Evolution of Life Frames: past, present, future in the Pavilion of the Earth can be described as ecologies: systems of people, plants, animals, diverse cultural, social and art practices and public pedagogies. Bonnie Sherk refers to her practice as ‘life frames’. This idea, as she explains in a video interview for the Biennale, started as placed-based performance-installations, still lives, like a portable park one, which evolved in more participatory performances and became The Farm: a place-based and community oriented process to transform multiple sites and humans.

As an artist, I have tried to expand the concept of art to include, and even be, life, and to make visible connections among different aesthetics and systems of knowledge. The most recent and devotional vehicle for this coming together is a multicultural, agricultural collaborative art work called Crossroads Community, or more simply, The Farm. (1977: 227).

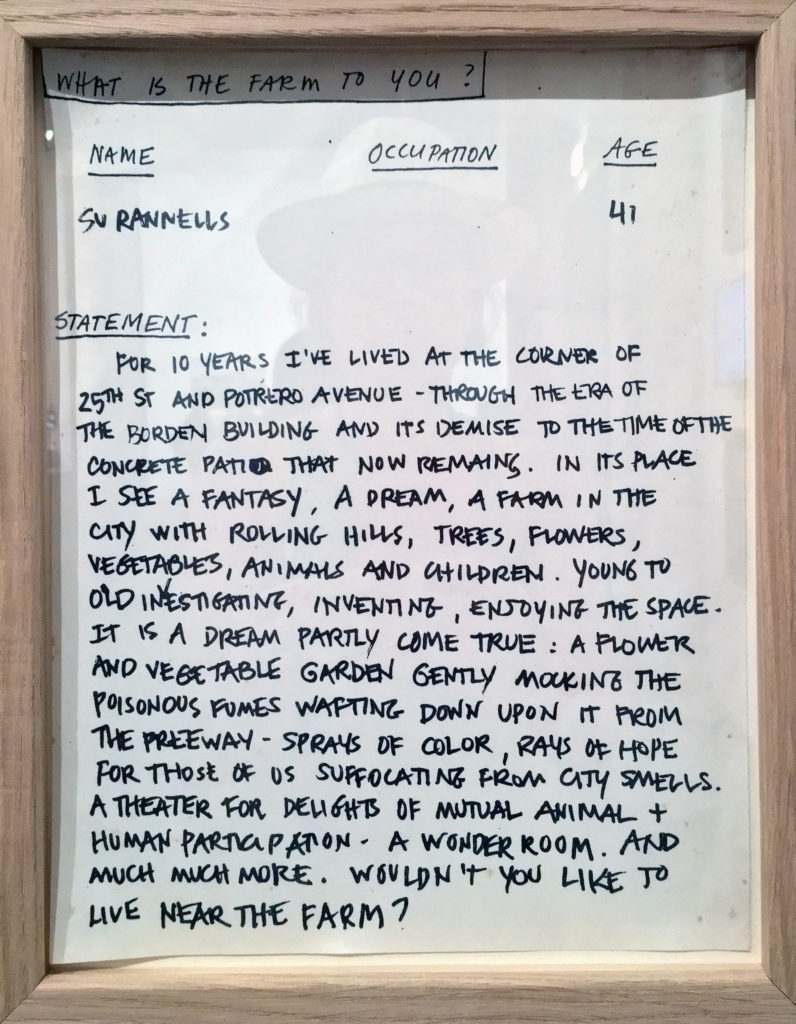

The Farm, as you can see in a video with original footage from the mid-1970s here, was a complex project that created urban commons in San Francisco by means of urban farming, theatre, environmental art, literature, community cultural development and education. It included a preschool, a library, a kitchen, a farm, and performance spaces. It was situated at the crossroad of four low-income and culturally diverse communities, under a major freeway interchange, and it was described as culture-ecology park to educate people about integrated systems and as a life-scale sculpture.

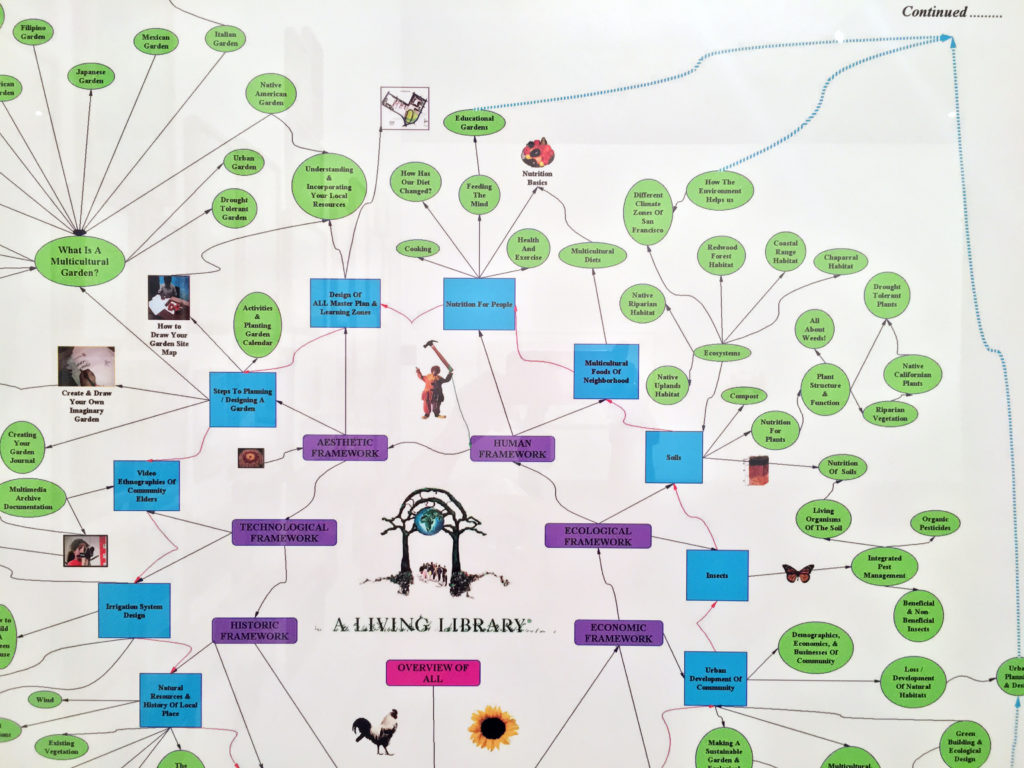

The methodology of life frames that pervaded The Farm developed to become interactive community programs, interdisciplinary and practice-based learning integrated in specific places. A Living Library, the second project presented in Venice, ‘it’s a vehicle for helping us to understand interconnected systems: biological cultural and technological. Life frames work with diverse communities and schools in making ecological transformation that is then systemically integrated with hands-on community programs or learning opportunities … I call this work a systemic ecological design and it’s really a way to bring local resources together and use them to transform places. A very powerful planning tool that I developed which I call a living library framework links local resources: human ecological economic historic technological and aesthetic. When we look at these assets through the lens of time, past present and future, we find incredible richness wherever we are and a lot of content to work with. This then results in the transformation of beautiful places that are systemically integrated with hands-on programs that relate to multiple issues like climate change, community education, flood mitigation, environmental justice, green skills job training and other related issues’. (Biennale Arte 2017)

This is important because the methodology of the work performs its content: ecology, and system thinking, is both the matter and the process:

Everyone and everything on Earth and in Space is part of A Living Library of diversity: people, birds, trees, air, water, and all the things we create, such as – parks, gardens, schools, curricula, artworks, networks, communities, celebrations. A Living Library, or, A.L.L., for short, provides a way to understand that culture and technology are part of nature. It’s all nature. (A Living Library =A.L.L.)

A Living Library was a strange encounter at Arsenale: in the misdt of a rather woolly (literally) curatorial narrative I thought I had found my tribe (well, I also thought Maria Lai posthumous installation was my tribe). This despite the obvious issues of exhibiting a metonym of a much more complex and living work: a life frame, as Sherk may put it.

Biennale Arte 2017 2017, Bonnie Ora Sherk, viewed 29 October 2017, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VIXkaySpH90>.

Sherk, B. 2007, ‘Position Paper: Crossroad Community (The Farm)’, in W. Bradley & C. Esche (eds),Art and social change: a critical reader, Tate Publishing, London, pp. 227–9.

0 Comments