We presented a paper at the conference Tropics of the Imagination in Singapore last week, and took occasion to think through what kind of tropical imaginaries are generated by plants. We started by locating our work in Gadigal country, specifically in Marrickville, explained our methodology, introduced which tropical tropes are associated with plants, and concluded following the trajectories and assemblages of three plants: banana trees, papaya trees and dragon fruit.

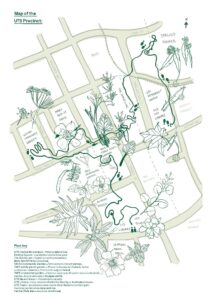

In this work we used ethnographic and design research methods, such as iterative ways of walking and mapping neighbourhoods These walks help us identify human and non-human participants and issues of concern. We usually think of this process as walking with plants. For this paper, we were led by tropical plants. Walking generates particular questions and opens up a multispecies sensory ethnographic practice (which we have written about in some of our posts at the WalkingLab). The occurrence of particular plants that we noticed and mapped as we walked in the disturbed landscapes of Marrickville – a hybrid suburb, where the industrial present meets the gentrified future – guided us to develop a specific focus on abundance.

Rather than being technically ‘tropical’ species, the plants we mapped included those we associate with the tropics such as papaya, banana, and dragon fruit. We define this state of things as the ‘not yet tropical’ of the city to indicate how the urban plantscape of Marrickville is adapting to rising temperatures and climate change, and how this acclimatization is made visible by the growth of tropical species.

As part of our practice we follow up these iterative walks with ‘over the fence’ conversations and then semi-structured interviews. In doing so we produce an audit of a place through the lens of plants. Another element in our methodology is to map our observations using Instagram as a note-taking tool, similar to what Tricia Wang defines as ‘live fieldnoting‘ and Map my Walk as a way to record our movements in space.

As we walk we also keep a research question tumbling at the back of our mind, which in this case was: how do plants enact geographical imaginaries, such as for instance ‘the Tropics’? We came up with two main tropes. The first one is the jungle horror: the tropics are shaped as the jungle, with wild, untamed, entangled, carnivorous, threatening, mysterious plants and animals that take over and ignore boundaries. Plants generate a sensory overload of colours, smells, and if one cares to taste, flavours. Because plants sprawl in a confused mess of leaves, branches and fruits they resist description, and because they are evergreen, they seem to suspend the rhythm of both seasons and suburban life. The weird and the monstrous may lurk at the edged of this trope, or as it is the case of the gardens we visited on the edge of ponds, fences, and footpaths.

The counternarrative to the jungle is the colonial kitsch. The tropics are imagined as colonised, as a anthropogenic landscape where the abundance of nature can be controlled, contained, fenced in and used for selective human benefit: think Balinese patios and giant Buddha’s heads. In some of the garden we visited this trope took an ironic turn, including pink flamingos, and the reworking of a fallen branch into a dinosaur, or perhaps snake.

However, these two tropes are generated by a very human-centred tropical imagination. Instead, we wanted to shift this perspective and argue that there are also multispecies ways to imagine the tropics. We asked: what happens if we draw from permaculture ethics and principles (earth care, people care, fair share, value the marginal, observe and interact, integrate don’t segregate) to reimagine the jungle and the colonial in terms of abundance?

Our research is revealing that this reimagining is happening through the way that plants engender everyday practices in the gardens of Marrickville as people are led by the plants that escape them, feed them, delight them, challenge and frustrate them. In Marrickville, as elsewhere, plants escape from gardens and are also found in industrial areas. Their seeds are carried by birds or bats or rats and they grow between buildings, around canals, and along train lines. Or they push through fences and across human-made borders, escaping and creating new edges.

Take bananas, for instance. They look tropical so much so that they symbolize the tropics. Many parts of the plant are used: the leaves to package and serve food, the flowers, the fruit as as a super food with its own waste-free packaging and as offerings. These practices travel with people as they settle and create the city, as we found out in our wanderings through Marrickville, where bananas are abundant. They are part of cultural and religious rituals, but they also do their own thing, taking over disturbed landscapes and forming very lush thickets.

As we followed bananas, we noticed other things and began learning more about them. Bananas are not true trees and they do not reproduce by seeds. The stems are made from layers of tightly packed leaf bases, and each new leaf comes up through the centre of the stem.They send out suckers that then escape gardens. They escape from cultivation in the city to occupy this wild grove along train lines, where they reclaim a disturbed a landscape. Once there, they protect taro, papaya, fennel and other species that dwell closer to the ground, and for as long as they are left alone, they keep spreading, untended. Humans are also part of the banana network, and some insert themselves in this plant’s migration, collecting particular species of bananas from the internet, or swapping with neighbours, or sharing suckers and of course hands of bananas after their harvest.

Papayas are one of those edible species, like chillis and lemongrass, ubiquitous in suburbs which are, or have been, home to Southeast Asian communities. Sydney is home to Australia’s largest Vietnamese community. Arriving as refugees and family reunion migrants after the fall of Saigon to advancing communist forces in 1975, the Vietnamese were the first large group of Asian immigrants to settle in Australia after the end of the White Australia policy, and the first significant group to arrive after the advent of official multiculturalism. Many settled in Marrickville and probably began cultivating papayas, or at least eating them and spitting out the seeds at the edges of their properties. There are as many stories as there are now papaya trees.

During one of our interviews, the papaya tree was one of our first talking points when the gardener we were visiting corrected our identification ‘Pawpaw, not papaya’, she said very pleased, as, she explained pawpaw and mango do not grow in Pescara, one the east coast of Italy, where she is originally from (whether picked green or ripe, papaya, pawpaw, or papaw are all from the same plant, Carica papaya The industry in Australia labels the red fleshed fruit from hermaphrodite trees as papaya and the larger yellow fleshed fruit from dioecious trees as pawpaw). The papaya tree came out of her compost, which means that she or one of her children probably made the choice to eat a papaya before she chose to grow it. Papayas also collaborate with other species, not just humans putting the seeds in their compost heaps. Bats and birds, for instance, help papayas to move across the urban landscape.

In Australia, we tend to think of dragon fruit (Pitaya) as a typically Southeast Asian tropical plant. It is actually a desert cactus that originates from Mexico, from where it was transplanted to other areas of Latin America by Europeans and beyond in South East Asia, USA, Israel, Cyprus, Canary Islands, and of course Australia. Like papaya, dragon fruit grows easily from seed and also from cuttings, and it has adapted well both to dry and tropical climate. Most interestingly, for us, it has made humans adapt, because pitaya needs a support to climb on. It puts out aerial roots, and once it reaches 10 kilos, it starts to flower, and relies on moths or bats for fertilisation.

Dragon fruit also relies on humans, who kindly co-design and build inventive supports, using whatever it is at hand. Sometimes a fence will do, but often wood planks, metal tubes, other plants are assembled to provide support following the growth path of the plant. Similarly, dragon fruit’s limbs break off easily, and are given from gardeners to other gardeners, generating connections and relations through a planty variation of the gift economy.

Dragon fruit, the way it enrolls humans, things, other plants, animals and insects also leads us to some concluding questions: what happens if we are led by plants into reimagining the tropical, as we have done here looking for instance at banana circles along the railway line; papaya popping up with the help of birds and humans along walls, near gutters, on the edge of parks, on compost heaps; dragon fruit -which is not tropical but behaves as if it were- creating sharing circuits and co-designing with their humans fantastic structures? Can plants help us imagining abundance as a kind of commons, unrecognised by urban renewal projects at a city scale nor by the global discourse of sustainability?

0 Comments