Reason is a seed because, contrary to what modernity has insisted on believing, it is not the space of sterile contemplation, not the space of the intentional existence of forms, but the force that makes it possible for an image to exist as the specific destiny of a given individual.

If we could think through plants, we would think very differently indeed. But because we are so desperate to communicate with each other, humans would still use metaphors and would still write poetry.

Written as a bridge between philosophy and botany, this book speculates on how we might see the world differently had we valued plants from the beginning. Coccia takes issue with the ways the disciplines of science have ‘… taken it upon themselves to transform nature into a purely residual, oppositional object, one incapable of occupying the position of subject.’ But he also reminds us of how human-centred the humanities really are.

Key to a philosophy grounded in understanding plants is the concept of immersion.

Plants show us the futility of thinking in terms of objects because they are immersed beings, in a fluid world in which everything is in motion. In such a world, the relationship between object and subject is impossible because the material distinction between us and the rest of the world fades away. ‘Permeability is the key word: in this world, everything is in everything.’ (32)

In order to break this down in human terms Coccia links the atmosphere of the world to dancing in a night club, where the eyes and ears and body are experiencing immersion. A custom designed space, that emphasizes atmosphere over sight, is a window into the life of plants, who are made by the same substance as the world around them.

The houses we make are also forms in which we project ourselves in order to make sense of the ‘sea in which we immerse ourselves’ (34). These links to the familiar and the designed are not only charming, they provide the reader with anchors for thinking through plants at our own scale and with the handicap of our individual bodies as vehicles. Plants, after all, can think together.

To be in the world necessarily means to make the world: every act of living beings is an act of design upon the living flesh of the world.’ (39)…

But this is not to make in the sense of transforming materials, communicating, using tools, or creating space, this is a ‘silent and mute design, an ontological design.

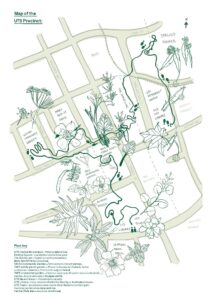

With their ‘plasmability’ plants show us the most radical design, by exercising on the world, not their will, but their being, on a global scale. Being in the world means to share the ambient space with an ensemble of other living beings, not to live in a house, or a community, or a neighbourhood.

Coccia’s desire to invent a new way of thinking about the world, to coin phrases and evoke images to describe the limitations and consequences of our human-centredness is a step in the right direction of multi-species philosophy. Plants are at the center of this thought experiment which is refreshing. But it does strike me how urban and European these ‘discoveries’ about plants are.

In a lovely review, Rachel Reiderer points out

It is hard for me to imagine a farmer or even gardener who would be surprised by any of the philosophy in Coccia’s book. But for those of us who live in concrete places and do not have many occasions to contemplate the logic of flowers or motivation of roots, it is a good reminder.

Rachel Reiderer, The Nation.

0 Comments