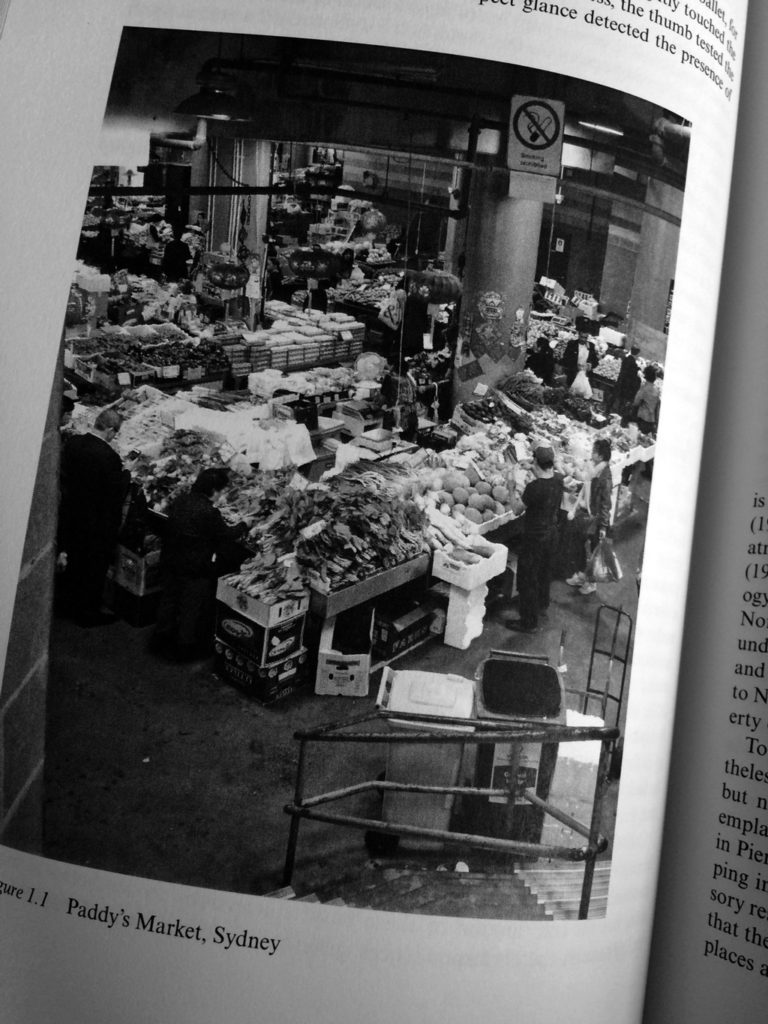

This is a book for travelers and observers of the world, especially people who are drawn to the challenges and contradictions of cities. Cities included are Hong Kong, Beijing, Rio de Janeiro, London, Antwerp, Amsterdam, Paris and San Francisco, but author Kirsten Seale begins in Sydney, at the markets with which she is most familiar. The messy, kitsch, and undeniably atmospheric Paddy’s Market offers a great starting point to pose the deceptively simple question ‘What is a market?’

Opposite our own library at UTS, Paddy’s is one of my most frequented marketplaces. I have bought party wigs, the hottest chilies I’ve ever tasted, and rose petal tea for staying calm in the office. Markets are personal, because we make them through our sensory engagement.

Paddy’s Markets

Seale artfully connects market with place as she describes her sensory research methods:

‘Certainly place has spatial dimensions, but it also emerges phenomenologically from the space of the market through making’. (4)

Seale knows what she does about markets through her own making of the marketplaces she visits. She participates in markets by buying, selling, looking, chatting, eating, touching, smelling, moving about, meeting up, hanging around etc. She also takes beautiful photographs, which are reproduced abundantly in the book and make a significant contribution to the story. Her own making of markets provides an important pivot point to explore the political dimensions to the relationship between markets, place and cities. Distinguishing between making place and placemaking, she describes each market she visits in great detail, working out whether it is contributing the the making of place, or being employed as a device in placemaking by branding urban renewal projects. Perhaps unsurprisingly, often it is doing both.

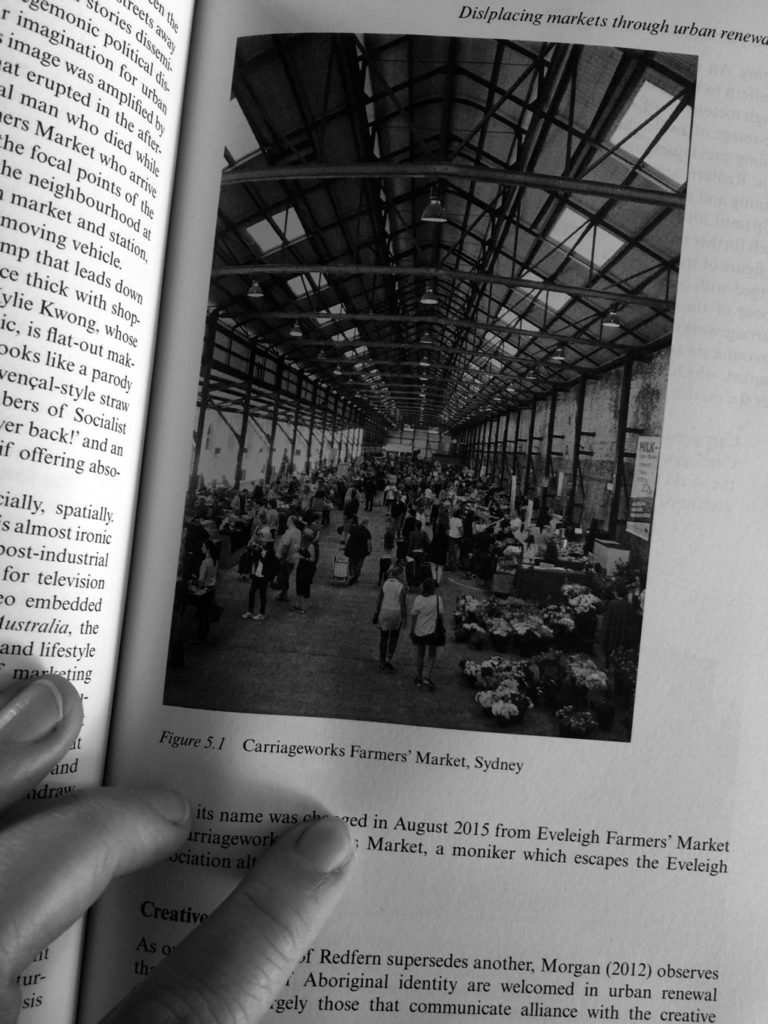

The closest examination of a particular market is also in Sydney, in Chapter 5, ‘Dis/placing markets through urban renewal’. It can be difficult to maintain critical faculties when thinking through the city one lives in. After all, these are usually the places we are most deeply invested in making. But Sydney offers such explicit examples of displacement and Seale employs them masterfully to interrogate the connections between markets, place and urban renewal. She points to the many ‘narratives of decline’ (72) that are used for strategic placemaking in this city, focusing on the history of displacement of Aboriginal people in Redfern and the rebranding of Eveleigh as a Creative precinct, now with a Farmer’s market. (For a very current example of the narrative of decline see the proposed urban renewal for Carrington Road and other industrial areas of Marrickville – perhaps the location of Sydney’s next artisanal marketplace.)

Carriageworks Farmers Markets

Markets are ubiquitous in global cities, and yet, they work in a variety of local ways to make place. Markets are often edge places, if not located literally at the peripheries of neighbourhoods, then operating at the edges of formal economies. These kinds of markets, those that are ‘heteregenous, liminal, improvisational’ (115), Seale argues are truly urban, and are best positioned to offer grounded and creative responses to the crises of cities.

0 Comments