We are in the habit of making maps, and putting them together as atlases. So we thought it was time to try to explain why.

An atlas is a book or collection of maps. Many atlases also contain facts and history about certain places. There are many kinds of specialized atlases, such as road atlases and historical atlases.

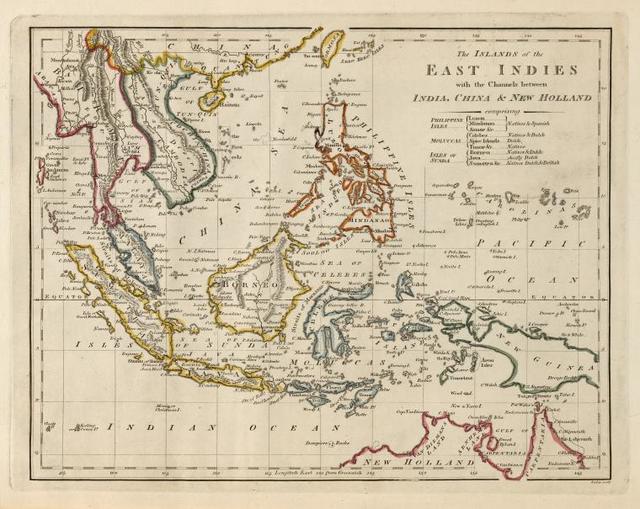

Maps and Atlases have been (and continue to be) tools of colonisation. There are innumerable examples, such as the empire building that created the Dutch East Indies by mapping and naming it, or the European maps of ‘Terra Nullius’ that colonised Aboriginal people in Australia.

The islands of the East Indies with the channels between India, China & New Holland. Public Domain, thank you NYPL

Many maps (as a form of visual communication) have been designed to create, enforce and manipulate colonial border systems that violently control people and Country. Many maps are visual translations of colonisation. The film by Warwick Thornton ‘We Don’t Need A Map’ is challenging and poetic counter example of design history that helps explain the role of maps in colonisation.

However, as feminist researchers who employ place-based methodologies, we also see the potential of maps and atlases to critique, shift visibilities, and even decolonise. We believe an atlas can do more than catalogue and archive the status quo. It can generate and reproduce new and necessary orientations that position human beings away from the centre of everything. We think about both maps and atlases as material forms to bring together diverse knowledges. Maps and atlases are not only visual tools, they are epistemologies. They can help us pay attention to the world using all our senses in order reorientate, navigate and take action as political bodies in an ecological crisis.

We propose that to make recombinant ecologies present, as well as visible in the lives of humans living in cities, we need a different order of maps. Maps able to (metaphorically) move observers away from their hovering position, place them back in the thick of things, and let them be led by the more-than-human gatherings that recombine in city ecologies.

An atlas can connect space and time in new ways. An atlas can articulate the coalescence and collision of local and global trajectories, described by the late Doreen Massey as ‘throwntogetherness’. Massey describes how different elements and trajectories – human, more-than-human, social, cultural and political – come together to define a here and now. In this understanding, space is not limited to specific areas or points on a map, instead it is produced by the encounter of multiple local and global trajectories which have also a temporal dimension.

We pay respect to our feminist peers who use maps and atlases in creative and decolonising ways, Shannon Mattern, Rebecca Solnit, and one of our current favourites, The Feral Atlas curated and edited by Anna L. Tsing, Jennifer Deger, Alder Keleman Saxena and Feifei Zhou.

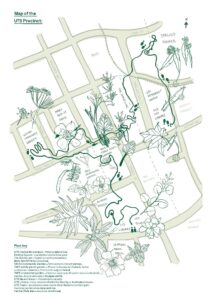

In 2019, we made The Planty Atlas of UTS, which expanded the map into an installation, a catalogue of learning resources, and series of walks. We are currently working on The Green Square Atlas of Civic Ecologies, a project that will connect everyday acts of environmental stewardship to ecologies, cultural histories and preferred futures.

The Green Square Atlas of Civic Ecologies is another resource to rethink place and visual systems.

0 Comments