This edge is a precarious one. The paperbarks, ironbarks and fig trees around Sydney Park are marked for demolition: WestConnex, the major toll motorway project planned by the NSW State government, advances. Nobody, including the government’s own modelling, is quite able to explain what the benefits of an interchange in the South side of the city are going to be. The damage already done and that will be done, on the other hand, is evident. The WestConnex Action Group does an excellent job at keeping the information flowing, as well as at keeping the protest going. Wendy Bacon has investigated WestConnex planning processes, and written about the protests and the resistance against development and consequent loss of low income housing across Sydney from Redfern and Waterloo to Millers Points, loss of heritage buildings and local history in Haberfield, and loss of biodiversity along the Cooks River. Vanessa Berry, in one of the most powerful and evocative essays possibly ever written about Sydney, offers a different kind of excavation of St Peter, one where the trajectories of Campbell Road, its houses just before they were demolished, the Alexandria Canal (all of which inspired Nadia Wheatley’s My Place) come together in a cultural history of what Berry calls ‘a typical St Peters scene: unlovely, surreal, resistant to investigation.‘ St Peter, she reminds us, is a recent invention:

‘For thousands of years, like much of what is now known as Sydney, this area was forest. Colossal turpentine and ironbark trees made up the canopy and the forest sloped down to marshland and a winding saltwater creek. The Gadigal, whose country is this place, walked the track that ran across the top of the ridge and hunted kangaroo in the forest. Then the land was invaded by the British, who stripped its trees and turned the earth inside out. The rich clay soil that once nourished the forest was found to be good material for brickmaking. From the 1830s brickworks multiplied, hollowing out the land with deep excavations. As the city climbed upwards and radiated outwards, its buildings took shape from bricks made of St Peters earth’.

Like then, destruction is palpable on this edge now. Like then trees have been, and will be, cleared. As I walk along Sydney Park Road I am overwhelmed by a sense of loss to come, a future grieving. This edge is precarious: trees will be gone, their ecosystems will ben gone, the bacteria, fungi, bugs, birds and animals that live in this edge will be gone, just like people’s homes have gone at the other end of the park. So I grieve the imminent loss of biodiversity, but also of a bio-social space of plants and humans, and of everyday habits, because the interchange will replace all the existing trajectories that animate this space.

Grieving, Lesley Head argues in her book Hope and Grief in the Anthropocene, is part of the cultural politics of responding to climate change. Head writes that we grieve for the loss of conditions that make life as we know it possible. This grief is paired by an opposite tendency towards hope, that leads to focus on action, positive outcomes, policies. This tendency is according to Head, akin to denial. Staying with the grieving is a necessary political stance. Grief, she writes ‘is not something we can deal with and move on from, but rather something we must acknowledge and hold if we are to enact ant kind of effective politics.’ (2)

Dipesh Chakrabarty in a recent lecture at the Climate Justice Research Centre at the University of Technology Sydney, pointed out that both gloom and doom and the search for more optimist stories are part of the same strategy to bring back climate change to human time: to something that can happen within one’s life. This attempt to anthropomorphize is also an attempt to fold things back into human history and power dynamics: the human ability to affect the environment. The environment and the planet, is implied here, might actually give zero fucks and continue at their own, slow pace.

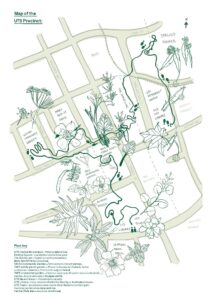

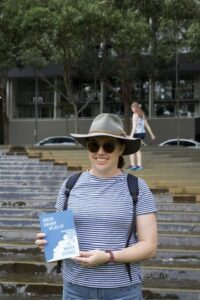

Yet grieving, and related anthropomorphizing of trees and nature, is part of the political landscape of displacement brought about by the NSW State Government. So I wander with these two sets of ideas in mind, and wonder how these affects – hope, grief, optimism, gloom – materialize around me in the limited time and space of a walk in Sydney Park. I also wonder how politics and the political emerge among trees, protest signs, the camp, dogs walking, joggers, activists, cups of tea, and security guards. For the record I photo-document all the elements and instances that affect me. What follows is a visual audit.

It’s the blue. Blue becomes a signifier of the scale of destruction along Sydney Park Road, in the park itself, and in the streets around it. Blue, the brand colour of WestConnex, takes over public land and public green, turning community infrastructure into private corporations. Visually the blue fabric creates a perimeter of grief: trees for demolition are marked with blue sashes, and trees have a strong emotional pull. Trees on the death row, trees to be hugged, trees to be decorated and celebrated, trees to be rescued, trees to be adopted: ‘Save Me From WestConnex’ is stencilled on some of the WestConnex blue sashes. Politics is inscribed clearly in the words, slogans, leafleats, around the park. But the political is also deployed through affect, in the same mix of hope and gloom that one imagines must grip the (anthropomorphized) trees leading them to plead: Save Me From WestConnex.

On the corner closer to Alexandria activists have set up a protest camp. Here trees are decorated with multicoloured scarves and flags: other affects. I meet welcoming people who mind the camp, generous with their knowledge, their time, their space and their food. A sign invites to join the volunteers who keep watch 24/7 to protect this place from government vandalism. That’s where hope and grief are entangled.

Berry, V. 2016, ‘Excavating St Peters’, Sydney Review of Books, 28 September.

Head, L. 2016, Hope and Grief in the Anthropocene: Re-Conceptualising Human-Nature Relations, Routledge, London and New York.

0 Comments