Reposted from The Australian Interestingness Thank you Thomas Lee.

In the introduction to James Hull and Bede Brennan’s Shit Gardens, the authors spell out an ambivalence concerning aesthetic evaluation that is core to the concept and production of the book. For the authors, ‘shit’ describes gardens which might initially appear “inexplicably bad”, then, with time, come to be appreciated and inspire wonder. For Hull and Brennan, this sense of wonderment is provoked by the juxtaposition of “grand ambitions of intent with the inelegance of unfinished reality”, or what Peter Sloterdijk has described as the “aesthetics of disappointment”, which he argues characterises modernity more broadly (2013, 771).

However, it would be wrong to see these suburb delights as failures in any straightforward sense. As the authors stress, shit gardens are not “shit as a result of neglect”, but due to enduring departures from perfect from, whether through “a misunderstanding of scale, an appreciation for the weird, or bold disregard for convention.”

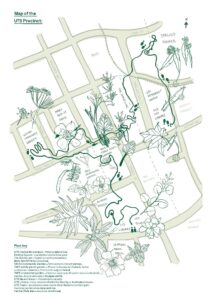

The book is the product of walks through suburbia and, to some extent, the fact that now most people, whether they intend to take photos or not, find that they happen to have a camera in their pockets if they want to fulfil the seemingly impossible to resist demand of being contactable all the time. The authors have a hugely popular Instagram account @shitgardens, which has over 50,000 followers, a bunch of whom are credited with the photographs used in the book.

As tech commentator Ben Evans has noted in 2015, internet enabled image sharing exists on a historically unforeseen scale. As Evan writes, according to Kodak, in 1999 consumers took around 80 billion images. In 2015 the inevitably inexact number is somewhere between 2 and 5 trillion, which doesn’t include the images taken and not shared. That seems to suggest a difference in kind, rather than degree.

Shit Gardens is in part a product of this socio-technical ecology, which is composed of the camera enabled smartphone, image sharing services such as Instagram, internet infrastructure and the communities that participate in this unprecedented flow of images. The mundane is under surveillance, not by the hierarchically organised, Orwellian systems of power, but by people taking their evening walks and getting a little buzz out of sharing minor wonders with a remotely present crew.

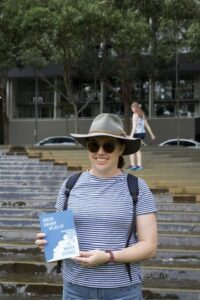

Like the authors’ conception of ‘shit’, publishing a book is an exercise significantly informed by duration. Lots of people have hypothetical, imaginary books which they are going to write or might have written. But the distance between thought bubble and the horizon to completion can be a long and barren stretch, with few cairns along the way to reassure those who take the path that they are on the right track.

That is, until the internet. Blogs and social media have to some extent enabled writers and cataloguers to immediately connect with a public and then sense whether their ideas are worthy of a book—as though a book, oddly, in this digital age, were still a crowning glory, the seal of approval on what would otherwise just enthusiasms. The immediacy with which information can be published significantly reduces the burden of having to invest time and emotional effort into something that might not deliver a reward. It changes the hedonic nature of the performance of writing or curating. Now the pleasure of making oneself known and yet obscure to world at the same time—traditionally a relatively exclusive pleasure for published writers—is an ambient availability for anyone who can afford or steal a smartphone. Instagram can provide that often sorely needed little hit of public affirmation on the long trail to the traditionally more auspicious occasions of a gallery opening or book launch.

But it would be wrong to therefore presume books like Shit Gardens are without generic precedent before the digital age. Clearly there are forceful echoes of the Wunderkammer, or cabinet of curiosities, in this work. The book is a collection of irregular gems. There is no proof here of god’s work in the universal oneness of things. Rather, what Shit Gardens proves, or rather celebrates, is the sometimes near pathological activity of humans operating autonomously from intelligent design. There are suggestive principles of order, but these are overlaid thematically by the authors according to diverse criteria. The chapters include: Topiaries (100% Plant-Based Surrealism), Gardens of Antiquity (Sentimental Statuary), Astroturf (The Future of Lawn), Hard Surfaces (High-Performance Concrete), Water Features (From Atlantis to the Present), Zen Gardens (The Suburban Minimalist), and WTF (Rethinking the Absurd). The best of which in my opinion is the chapter on Water Features. There is something about the detail and aspirations of these sculptural works that seems to paradigmatically express the sentiments of the book. And they photograph particularly well.

Paul Barker’s brilliant The Freedoms of Suburbia is a more recent precedent. Parker’s work is, like Shit Gardens, a defence of the diverse, vernacular adaptations which suburbia seems to afford. In contrast to the commonly held notion that postwar urban developments are lifeless places, both these books suggest that character is a quality that trumps beauty.

Shit Gardens is a affirmation of Daniel Harris’ argument that the aesthetic is “entirely indiscriminate in its choice of venue” (2001, xi). This has always to some extent been the case. However, the recent explosion of contexts for ‘hanging’ or posting works and the proliferation of communities devoted to aesthetic judgement means that it has become explicit and what we mean by aesthetic judgement is changing as a result. Hence Shit Gardens: which joins the countless books on gardens informed by the aesthetic of the beautiful, the sublime or the picturesque.

While the paradoxical vagueness and forcefulness of ‘shit’ as an aesthetic evaluation makes it perfect for an Instagram handle, it is actually the aesthetic category of ‘the interesting’ which in some senses more accurately captures the principles of discrimination, order and feeling at work in the book. As Sianne Ngai notes in her work on minor aesthetic categories, the interesting is an aesthetic which gives place to the role time plays in aesthetic judgement:

In contrast to the once-and-for-allness of our experience of, say, the sublime, the object we find interesting is one we tend to come back to, as if to verify that it is still interesting. To judge something interesting is thus always, potentially, to find it interesting again. In contrast to the “suddenness” Karl Heinz Bohrer celebrates as the essence of the aesthetic relation, here aesthetic experience seems narrativized or to unfold in a succession of episodes. (786)

The interesting is in abundance in a media ecology where cumulative catalogues of always accessible, different yet similar, aesthetic experiences are available in your pocket. As Ngai emphasises, the interesting is episodic. Its meaning is not in singularity but in the series. In this sense shit gardens become interesting not so much in themselves alone, as forceful, inescapable events of great magnitude and unforeseen meaning, but as a catalogue of impressionistically or analogically related types.

When Hull and Brennan note in their introduction that the shit-ness of shit gardens transforms from mild repulsion or puzzlement to perhaps equally mild wonder, they are describing a process that is very different to the idea of an sudden, emphatic, immediately transformative aesthetic experience associated with the sublime, and the more purely and straightforwardly pleasurable feelings that typically accompany the beautiful. The caveats the authors make concerning the question of aesthetic judgement at the beginning of the book indicate that the gardens they have chosen in some sense thwart or resist immediate judgement. On first glance they might strike us a shit, but then a different, more complicated sentiment emerges, as we attempt to integrate expectations of perfection with an imperfect reality, after which we might experience feelings of sympathy, or even reverence, at ingenuity, diversity, perversity, audacity, sentimentality, indifference to standards and the peculiar interpretation of standards.

List of works cited

Barker, Paul. The Freedoms of Suburbia. London: Frances Lincoln Limited (2009).

Evans, Benedict, “How many pictures?” August 27, 2015. Available from, https://www.ben-evans.com/benedictevans/2015/8/19/how-many-pictures

Harris, Daniel. Cute, Quaint, Hungry, and Romantic: The Aesthetics of Consumerism. Da Capo Press (2000).

Ngai, Sianne. Our Aesthetic Categories. Cambridge: Harvard University Press (2012).

Sloterdijk, P. Spheres Volume II: Macrospherology Globes, translated by Wieland Hoban. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press (2014).

0 Comments